Anxiety is ubiquitous to the human condition. From the beginning of recorded history, philosophers, religious leaders, scholars, and more recently physicians as well as social and medical scientists have attempted to unravel the mysteries of anxiety and to develop interventions that would effectively deal with this pervasive and troubling condition of humanity. Today, as never before, calamitous events brought about by natural disasters or callous acts of crime, violence, or terrorism have created a social climate of fear and anxiety in many countries around the world. Natural disasters like earthquakes, hurricanes, tsunamis, and the like have a significant negative impact on the mental health of affected populations in both developing and developed countries with symptoms of anxiety and posttraumatic stress showing substantial increases in the weeks immediately following the disaster.

Anxiety disorders are the most common mental health disorders in the United States, affecting approximately 40 million adults each year. The most common types of anxiety disorders are generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder.

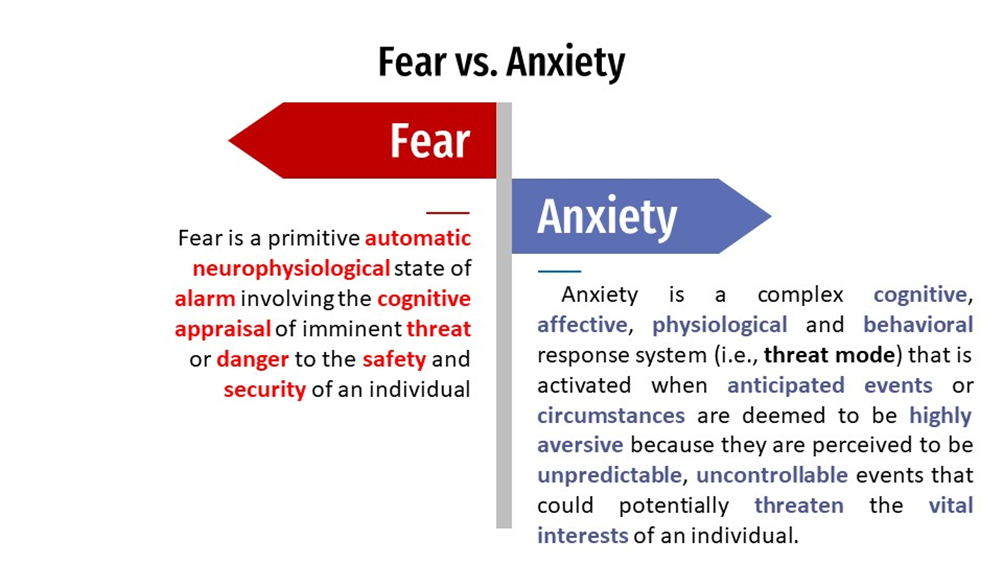

Anxiety and Fear

All emotion theorists who accept the existence of basic emotions, however, count fear as one of them. As part of our emotional nature, fear occurs as a healthy adaptive response to a perceived threat or danger to one’s physical safety and security. It warns individuals of an imminent threat and the need for defensive action.

Many different words in the English language relate to the subjective experience of anxiety such as “dread,” “fright,” “panic,” “apprehension,” “nervous,” “worry,” “fear,” “horror,” and “terror”. This has led to considerable confusion and inaccuracy in the common use of the term “anxious.” However, “fear” and “anxiety” must be clearly distinguished in any theory of anxiety that hopes to offer guidance for research and treatment of anxiety.

What triggers anxiety?

Anxiety rarely pops up out of nowhere; it’s usually triggered by an external situation or a thought, image, memory, behavior, or physical sensation. Most people find it quite easy to identify their anxiety triggers, especially if it’s an external situation or circumstance. Other times the trigger may be less obvious. This is especially true when it’s a thought or physical sensation.

Three types of anxiety triggers are indicated in the following questions:

- Did you find yourself in a situation or circumstance that made you feel anxious?

- Did a thought, image, or memory suddenly pop into your mind that caused you to feel anxious or worried? These are called unwanted intrusive thoughts.

- Did you feel some unexpected pain, ache, or other physical sensation that provoked your anxiety?

How much anxiety is too much?

It would be difficult to find someone who hasn’t experienced fear or felt anxious about an impending event. Fear has an adaptive function that is critical to the survival of the human species by warning and preparing the organism for response against life threatening dangers and emergencies. Moreover, fears are very common in childhood, and mild symptoms of anxiety (e.g., occasional panic attacks, worry, social anxiety) are frequently reported in adult populations. So, how are we to distinguish abnormal from normal fear? At what point does anxiety become excessive, so maladaptive that clinical intervention is warranted?

We suggest five criteria that can be used to distinguish abnormal states of fear and anxiety. It is not necessary that all these criteria be present in a particular case, but one would expect many of these characteristics to be present in clinical anxiety states.

Criterias

1. Dysfunctional cognition. A central tenet of the cognitive theory of anxiety is that abnormal fear and anxiety derive from a false assumption involving an erroneous danger appraisal of a situation that is not confirmed by direct observation (Beck et al., 1985). The activation of dysfunctional beliefs (schemas) about threat and associated cognitive-processing errors leads to marked and excessive fear that is inconsistent with the objective reality of the situation.

2. Impaired functioning. Clinical anxiety will directly interfere with effective and adaptive coping in the face of a perceived threat, and more generally in the person’s daily social or occupational functioning. There are instances in which the activation of fear results in a person freezing, feeling paralyzed in the face of danger (Beck et al., 1985). Barlow (2002) notes that rape survivors often report physical paralysis at some point during the attack. In other cases the fear and anxiety may lead to a counterproductive response that actually increases risk of harm or danger.

3. Persistence. In clinical states anxiety persists much longer than would be expected under normal conditions. Recall that anxiety prompts a future-oriented perspective that involves the anticipation of threat or danger. Thus it is not uncommon for anxiety-prone individuals to experience elevated anxiety on a daily basis over many years.

4. False alarms. In anxiety disorders one often finds the occurrence of false alarms, which is defined as “marked fear or panic [that] occurs in the absence of any life-threatening stimulus, learned or unlearned”. The presence of panic attacks or intense fear in the absence of threat cues or very minimal threat provocation would suggest a clinical state.

5. Stimulus hypersensitivity. However, in clinical states fear is elicited by a wider range of stimuli or situations of relatively mild threat intensity that would be perceived as innocuous to the nonfearful individual. For example, the number of spider-related stimuli that elicits a fear response in the phobic individual is far greater than the spider-related stimuli that would elicit fear in the nonphobic individual. In the same way individuals with an anxiety disorder would interpret a broader range of situations as threatening compared to individuals without an anxiety disorder.

How long does anxiety last?

The duration of an anxiety disorder varies from person to person. Some people may only have symptoms for a few months, whereas others may suffer from anxiety disorders for years, if not decades. A variety of factors can influence the duration of an anxiety disorder, including:

- The nature of the anxiety disorder. Some anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, have a shorter duration than others, such as generalized anxiety disorder.

- The seriousness of the symptoms. People who have more severe anxiety symptoms are more likely to have long-term issues.

- Other mental health conditions are present. People who suffer from anxiety disorders are more likely to suffer from other mental health issues, such as depression or substance abuse. These conditions can exacerbate anxiety and make treatment more difficult.

- The person’s ability to face others. People who have good coping skills can manage their anxiety better and are less likely to have long-term problems.

- The treatment’s efficacy. The most effective treatment for anxiety disorder is cognitive behavioral therapy.

Source:

Clark, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (2023). Anxiety and Worry Workbook. Guilford Publications.